#PSOTU18 Story Circle Training January 11 (SESSION FULL)

#PSOTU18 Story Circle Training Dec 11

#PSOTU18 Story Circle Training November 29

Honor Native Land: Steps Toward Truth and Justice

In early October, the USDAC released Honor Native Land: A Guide And Call To Acknowledgment, a free, downloadable Guide created in partnership with Native allies and organizations. It offers context about the practice of opening events by acknowledging the traditional inhabitants of the place, gives step-by-step instructions for how to begin wherever you are, and provides tips for moving beyond acknowledgment into action. If you haven’t already downloaded your Guide, visit the web page to access it along with customizable posters acknowledging Indigenous lands, and a short video featuring Native artists and activists.

Acknowledgment by itself is a small gesture. It becomes meaningful when coupled with authentic relationship and informed action, as an opening to greater public consciousness of Native sovereignty and cultural rights, a step toward equitable relationship and reconciliation. On October 17, the #HonorNativeLand campaign was featured on Native America Calling, broadcasting on over 70 public, community, and tribal radio stations in the United States and in Canada. Listen to the recording featuring USDAC Chief Instigator Adam Horowitz, Mary Bordeaux (Sicangu Lakota) of Racing Magpie, the artist Bunky Echo-Hawk (Pawnee/Yakama), Ty Defoe (Ojibwe/Oneida) and Larissa FastHorse (Sicangu Nation Lakota) of Indigenous Directions to learn more about the practice of acknowledgment and what it means.

Keith BraveHeart's poster for #HonorNativeland

As part of the broadcast, some recorded acknowledgments were shared. Here is Nick Estes (Lower Brule Sioux Tribe), a doctoral candidate in American Studies at the University of New Mexico, introducing scholar Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of numerous books including An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, at an event in Santa Fe, NM, sponsored by the Lannan Foundation. (Find that recording here.)

Hau Mitakuyapi. Nape Cuzayapi. Cante Waste. I greet each one of you as a relative, with a handshake, and an open heart and mind. As a Lakota person who is a guest in this place, I’d like to recognize the land belonging to the original people. This place is known to the Tewa-speaking people in their language as Kua'p'o-oge, “the white shell water place.” Here, a sacred hot spring existed, a Pueblo holy site, that Spanish settlers destroyed to erect the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. But Pueblo people remember this is their land and so must we.

Seventy-five organizations have already signed the USDAC’s pledge to make acknowledgment a regular practice:

As a step toward honoring the truth and achieving healing and reconciliation, our organization commits to open all public events and gatherings with a statement acknowledging the traditional Native lands on which we stand. Such statements become truly meaningful when coupled with authentic relationships and sustained commitment. We therefore commit to move beyond words into programs and actions that fully embody a commitment to Indigenous rights and cultural equity.

Signers include a range of local and national nonprofits, arts organizations, and education institutions, such as: the New Economy Coalition, Women of Color in the Arts, Arts in a Changing America, ArtWell, Barefoot Artists, Emerging Arts Leaders/Los Angeles, Arts in a Changing America, The Field, Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, The Natural History Museum, Peñasco Theatre Collective, and Alverno College International & Intercultural Center.

Imagine cultural venues, classrooms, conference settings, places of worship, sports stadiums, and town halls acknowledging traditional lands. Millions would be exposed—many for the first time—to the names of the traditional Indigenous inhabitants of the place they stand, inspiring them to ongoing awareness and action. Join us in sparking this movement by urging organizations you take part in to take the pledge now!

Jamie Blosser, Executive Director of the Santa Fe Art Institute, shared her experience of acknowledgment, which sprang from the realization that this is everyone’s responsibility, not just Indigenous people’s:

The Santa Fe Art Institute is new to this process, which I see as ongoing. We began the practice of acknowledgment after a couple of our Indigenous Canadian artists in residence approached me, asking why we were not acknowledging traditional territories at public events. They said the practice was now considered protocol at all Canadian events, but it was an entirely new concept to me at the time. I realized that—although my work prior to SFAI was primarily focused on affordable housing and cultural sustainability with Native American communities—I had always respectfully relied on my Indigenous friends and colleagues to set the tone and carry out acknowledgments. As this was all being discussed during the wintry protests at Standing Rock, with all of the world bearing witness to the courageous water protectors, it felt urgent to take on, both from a personal and institutional perspective.

Although we are seeking more guidance to make sure that our acknowledgment is appropriate, we are kept on track with this process by people who have approached me to say that SFAI doing this is affirming for and important to them. This kind of feedback has helped me to realize we need to make it more of an institutional imperative. I feel it sets a beautiful tone of reconciliation that we all need.

I am in such gratitude for the patience and kindness shown by my Indigenous friends and colleagues as this practice unfolds for SFAI, and as we make mistakes as we step into it. I ask for ongoing assistance, feedback, and collaboration to ensure it is a meaningful practice moving forward.

Bryan Parker's poster for #HonorNative Land

Sometimes actually doing something unfamiliar opens new pathways to understanding. Bay Area artist Cynthia Tom shared her experience of acknowledgment:

I am particularly tied into the Asian American arts communities in the Bay Area. I announced the acknowledgment project and mentioned the Coast Miwok Native people at the opening of “Hungry Ghost” (see A Place of Her Own), an exhibit that recently opened at Gallery Route One in Pt. Reyes, California. Much of what I curate has to do with helping artists heal by creating thought-provoking shows that provide a platform to share stories of ancestral, familial, gender, and cultural trauma. This includes historical references to colonization, forced migration, discrimination, violence, and the effects on long-term family patterns of trauma. I do this to help women artists and the community heal, increase consciousness around their own dysfunctional patterns and releasing them to move towards new ways of thinking; and to wake up the communities that surround us, to instill compassion, grow passion around various issues and civic engagement and a call to action.

The “Hungry Ghost” art exhibition brings up all these issues for the artists. If we are going to bring up colonization, I thought, how could we not address the deepest colonization of Indigenous land, closest to home? I always ensure we practice gratitude verbally and with print signage for each show, expressing thanks for our venue host, sponsors, donors, volunteers, artists, etc. I am excited to add #HonorNativeLand.

Cultural Agent Dave Loewenstein of the Lawrence, Kansas, USDAC Field Office described how acknowledgment led to a group of Kansans holding a much larger picture of the place they were living:

A couple years ago, I helped organize The Kansas People's History Project which aims to shine a light on lesser known stories about people and events from the state's past. When I went around Kansas giving presentations about how folks could get involved, I always started with a slide of a map of the state.

I said that the project was straightforward: just choose a person or event from Kansas that you feel needs more attention, write a brief narrative and illustrate it however you like.

And then I would pause...

Wait, I said, I need to clarify, because of course Kansas wasn't always Kansas. Before it became a state, it was part of the Kansas Territory. So, to be more accurate we'll call this The Kansas and Kansas Territory People's History Project.

Except...

Except, before Kansas was the Kansas Territory, it was part of Louisiana, so to be more inclusive we'll use the title, The Kansas, Kansas Territory and Louisiana People's History Project. Whew.

But...

But before Kansas was Louisiana it was (and still is) the home of the Shawnee, Ioway, Wyandot, Potawatomi, Kansa, Sac and Fox, Wichita, Osage, Delaware and many other Indigenous peoples.

In other words, when you think about it, this shouldn't be called The Kansas People's History Project. It should be called The Shawnee, Ioway, Wyandot, Potawatomi, Kansa, Osage, Sac and Fox, Wichita, Delaware, Kansas, Kansas Territory and Louisiana People's History Project.

Acknowledgment of ancestral lands is a small step, yes. But the truth has a way of expanding to fill the available space. If you aren’t already living into the truth embedded in the land you’re standing on, join us in taking the first steps by downloading the Guide, using the posters, and taking the pledge. You can find them all here.

NEW VIDEO: Highlights from CULTURE/SHIFT 2016

CULTURE/SHIFT was a national convening about Community Arts, Cultural Policy & Social Justice, held in St. Louis, Missouri in November 2016.

The event brought together some of the nation’s most creative thinkers and practitioners in a spirit of serious play and inclusivity.

Immediately following the presidential election, CULTURE/SHIFT 2016 generated and amplified creative strategies for change, bringing art to the heart of social justice and community. Through a rich mix of hands-on workshops, performances, interactive art-making, and public talks and actions, we explored how artists and allies can organize for full cultural citizenship.

Read our recap with links to plenary and workshop recordings and to more details about the convening.

Katrina, Sandy, and Now Harvey: How Can Art Help?

The National Hurricane Center has a penchant for friendly sounding hurricane names, but instead of generating smiles, the natural and by-now familiar responses are fear and compassion. This morning’s Washington Post predicts that more than 30,000 people from Houston and other towns in the region hit by Hurricane Harvey will be forced into temporary shelters as recovery gets underway. Our hearts go out to the people of Texas.

Immediate support is critical right now. Here are a few links people in our network have shared:

Another Gulf Is Possible: Collaborative for a Just Transition in the Gulf.

Circle of Health International: assisting mothers and children affected by Hurricane Harvey.

Coalition for the Homeless, Houston.

Portlight Inclusive Disaster Strategies.

Hurricane Harvey Community Relief Fund.

How can art help?

Citizen Artists across the U.S. have first-person experiences and wise counsel to share with their counterparts in Texas and those in other regions who are asking this question. USDAC folks on the ground in New Orleans and New York during Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy know that important questions need to be asked again, and that humane, creative responses are possible. How will survivors in temporary shelters be treated—and how should they be? Who will hear their stories and help them tell the world what they wish others to know? How can creative action help build resiliency and community in the aftermath of such a shock?

These and other key questions are covered in Art Became The Oxygen: An Artistic Response Guide, the USDAC’s free, downloadable resource for natural and civil emergencies, filled with inspiration, advice, and wisdom from artists and activists who know firsthand what they are talking about.

We invite you to read the Guide, and to view tomorrow’s Artistic Response Citizen Artist Salon featuring Carole Bebelle, Co-founder and Executive Director of Ashé Cultural Arts Center in New Orleans; Mike O’Bryan, Program Manager in Youth Arts Education at the Village of Arts and Humanities in North Central Philadelphia; and Amber Hansen, a co-director of Called to Walls and a visual artist based in Vermillion, South Dakota. You can join live online at 3 pm PDT/4 pm MDT/5 pm CDT/6 pm EDT on Tuesday, 29 August 2017 or wait and watch the recording later this week. (See our blog for tips on organizing a viewing party that can help local folks work together in artistic response.)

Here are just a few of the Guide's excerpts on storm-driven artistic response projects. The Guide contains many more details and links:

Evacuateer is a group that recruits, trains, and manages 500 evacuation volunteers called Evacuteers who assist with New Orleans’ public evacuation plan. They prepare and register evacuees, ensuring their ability to evacuate safely and with dignity.

Evacuspots mark the pick-up locations for the New Orleans City-Assisted Evacuation. Designed by public artist Doug Kornfeld, these 16 14-foot high stainless steel statues are created to withstand 200 years of wear and tear.

Alive in Truth was an all-volunteer project to record life histories of people from the New Orleans region who were affected “by Hurricane Katrina and the federal floods created by levee failure. Our mission is to document individual lives, restore community bonds, and to uphold the voices, culture, rights, and history of New Orleanians.” It was founded by Austin, TX-based writer, social justice activist, and educator Abe Louise Young, working with a large team of interviewers who captured stories. Each story link takes the visitor to a complete transcript with images.

Flood Stories, Too. This 2013 play by the Bloomsburg Theater Ensemble tells the story of the flood of 2011 caused by Tropical Storm Lee, in community members’ own voices. The production was a collaboration between BTE, the Bloomsburg University Players, and the Bloomsburg Bicentennial Choir. The script was based on hundreds of stories gathered from local residents via interviews and Story Circles; it incorporated original songs by Van Wagner and Paul Loomis. The staging resembled a church: seventy performers—children to elders, including some who’d lost their homes to the flood and many who’d taken part in cleanup efforts—were arrayed onstage on risers, the back rows of folding chairs holding Choir members, the other performers filling the front rows. Playwright Gerald Stropnicky, an emeritus BTE member, described the ultra-open casting philosophy: “a terrific cast of community volunteer actors joined the effort; the door was open to any and all willing to participate. No auditions, and no one would be turned away.” The box-office policy mirrored the casting: admission was on a pay-as-you-wish basis.

Photo posted by Vivian Demuth on Sandy Storyline

Sandy Storyline is widely admired as a rich repository of first-person stories relating to the experience of Hurricane Sandy, not just the immediate emergency of being displaced or injured, but also accounts of how the experience affected lives for years afterwards. The project was conceived and co-directed by Rachel Falcone and Michael Premo, working in collaboration with a large team and many sponsors and supporters.

The site puts it concisely:

By engaging people in sharing their own experiences and visions, Sandy Storyline is building a community-generated narrative of the storm and its aftermath that seeks to build a more just and sustainable future. Sandy Storyline features audio, video, photography and text stories — contributed by residents, citizen journalists, and professional producers–that are shared through an immersive web documentary and interactive exhibitions.

Park Slope Armory. Caron Atlas, Minister of Naturally Occurring Cultural Districts on the USDAC National Cabinet, lives in Brooklyn. She was deeply engaged in volunteering at the Park Slope Armory evacuation shelter following Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

In a Summer 2013 GIA Reader article, she described what happened and offered advice for future artistic response. At the invitation of a city council member, Caron, who directs Arts & Democracy, joining with artists and cultural organizations from the neighborhood and across the city,

created a wellness center in a corner of the armory drill floor, with programs that included arts and culture, exercise, massage, religious services, a Veterans Day commemoration, an election-watching party, film screenings, therapy dogs, AA meetings, and stress relief. In essence, the wellness center became the living room of the armory—a place where the residents could come to talk, reflect, create, build community, and even enjoy themselves. It served the staff and volunteers as well.

The article portrays in vivid detail the ways that many different artists—a jazz musician, a dancer, actors and others—interacted with shelter residents, becoming essential to the humane functioning of the facility and to the dignity, respect, and humanity of the residents. Comfort and care were important, but just as much, the work was to cultivate people’s agency to act and to advocate for those in the shelters.

Please share the Guide, take part in the Salon on August 29 or watch the video afterwards. Watch this space for more information about the USDAC’s Artistic Response work to come. Please feel free to get in touch with your own questions and stories about artistic response: hello@usdac.us.

#ArtResponds: Use Your Gifts for Awareness and Action in Charlottesville and Beyond

This past weekend in Charlottesville, VA, Nazis and their allies marched for white supremacy and Heather Heyer, one of the legions of human rights advocates who came out to oppose them lost her life to a terrorist who plowed his car into a crowd. Protest—along with care and consolation and building resilience—is one of the three aims of artistic response to civil or natural disaster in Art Became The Oxygen: An Artistic Response Guide; just enter your email to join a thousand others who’ve downloaded the this free 74-page Guide in the last week, and learn more about the models, methods, ethics, and awareness needed for effective artistic response.

Last week we wrote about the Guide as a whole. This week, our focus is on art that protests injustice, calling people to awareness and action. The USDAC is built on the principle that human rights are cultural rights are foundational human birthrights. Watch this Indivisible guide for solidarity events. Donate to the Solidarity C’ville anti-racist legal fund, Black Lives Matter C’ville, or other organizations that stand for equity, justice, and cultural democracy.

Once you download the Guide, be sure to join us at 3 pm PDT/4 pm MDT/5 pm CDT/6 pm EDT on Tuesday, 29 August 2017 for an Artistic Response Citizen Artist Salon featuring Carole Bebelle, Co-founder and Executive Director of Ashé Cultural Arts Center in New Orleans; Mike O’Bryan, Program Manager in Youth Arts Education at the Village of Arts and Humanities in North Central Philadelphia; and Amber Hansen, a co-director of Called to Walls and a visual artist based in Vermillion, South Dakota. Just enter your email to sign up and you’ll receive a link to take part in this online video conversation.

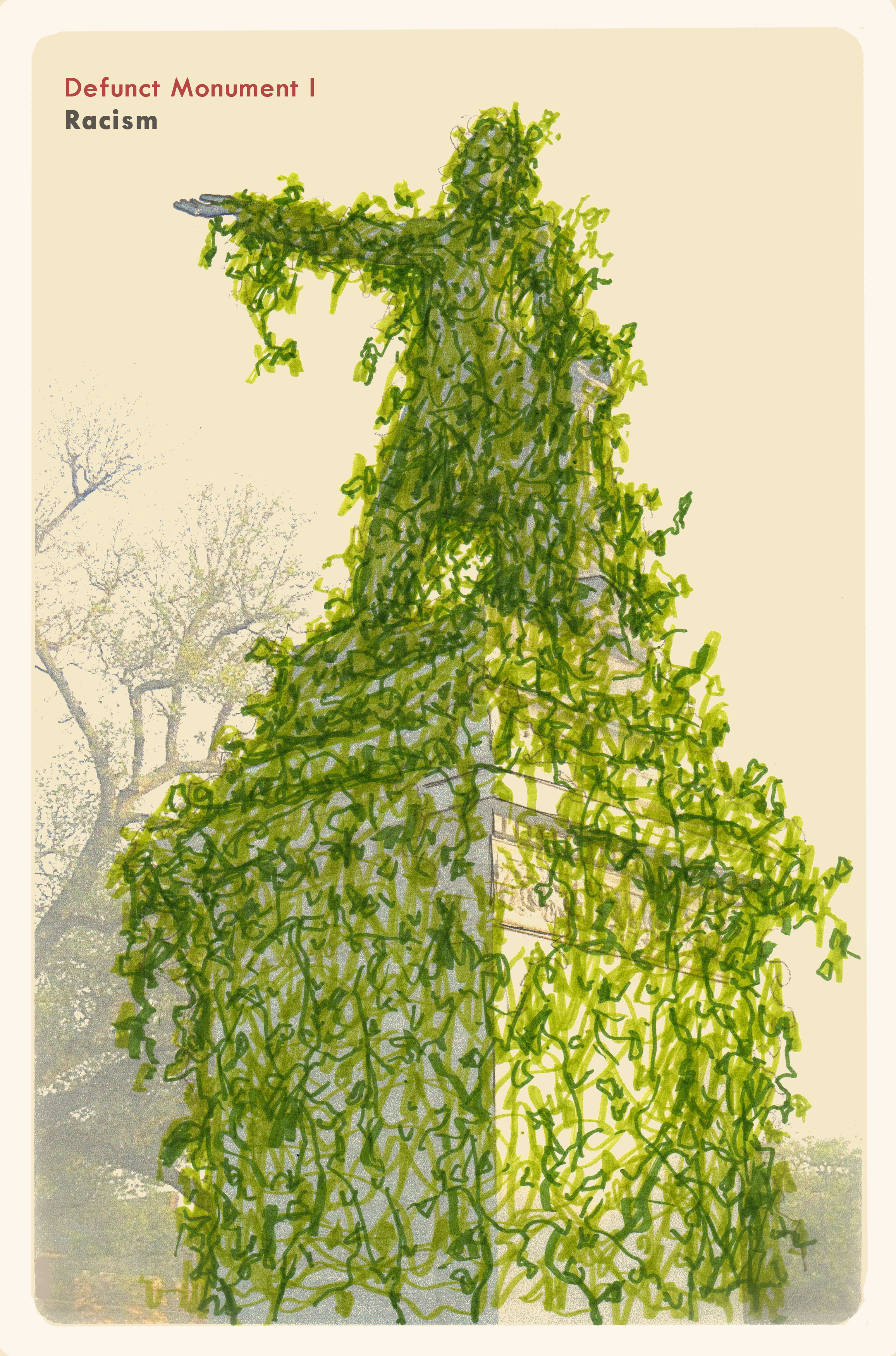

Cultural Agent Dave Loewenstein's vision of a monument to racism vanquished. See all three images in the series here.

What can Artistic Response do in moments such as these? As we say in the Guide,

As a vehicle of protest, artistic response can share the realities of those most directly affected by emergencies, countering cover-stories and distant analyses. It can reach people emotionally and somatically, as well as intellectually, adding impact. It can generate images, sounds, and other experiences that build awareness and lodge in memory, affecting future actions. It can illustrate what is broken and offer powerful images of healing and possibility.

Here are just a few of the Guide excerpts on protest-focused artistic response projects:

The Mirror Casket. De Andrea Nichols designed The Mirror Casket, a coffin faced entirely in mirrored glass, “to challenge on-lookers to question, empathize, and reflect on their own roles in remediating the crisis of countless deaths that young men of color experience in the United States at the hands of police and community violence.” The Mirror Casket was carried in many demonstrations before it became part of the collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. Here’s how De’s website describes the project:

The Mirror Casket is a visual structure, performance, and call to action for justice in the aftermath of the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. Created by a team of seven community artists and organizers, the mirrored casket responds to a Ferguson resident’s call for “a work of art that evokes more empathy into this circumstance” following the burning of a Michael Brown memorial on September 23, 2014.

With an aim to evoke reflection and empathy for the deaths of young people of color who have lost their lives unjustly in the United States and worldwide, The Mirror Casket was performed as part of a “Funeral Procession of Justice” during the Ferguson October protests. As community members carried it from the site of Michael Brown’s death to the police department of the community, its mirrors challenged viewers to look within and see their reflections as both whole and shattered, as both solution and problem, as both victim and aggressor. The Mirror Casket has since been used throughout related protests and marches.

Marching with The Mirror Casket.

#Icantkeepquiet: Every issue that encroaches on community and individual well-being stimulates protest art. Consider the song #icantkeepquiet, emerging from the Women’s Marches in January 2017. Los Angeles musician MILCK wrote the song and taught it online to a group of women who came together to perform it first during the demonstration on the streets of Washington, DC. It went viral on YouTube. The site makes sheet music and guide recordings freely available and collects stories of speaking out in the face of repression.

#WRITERSRESIST. Writers gathered in 100 events across the globe on January 15, 2017, the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., under the banner of #WRITERSRESIST, asserting their commitment to free, just, and compassionate democracy in the face of official actions that shake these commitments.

I Hear A Voice. In the summer of 2016, students in the Twin Cities Mobile Jazz Project summer school program created a song in tribute to Philando Castile, who was killed by police just days before. The track weaves snippets of news soundtrack, spoken word, and choral singing with instrumental music.

Social Emergency Response Centers. The Design Studio for Social Intervention has been experimenting with SERCs (Social Emergency Response Centers)…. You can see images and video describing the prototype center DS4SI piloted in 2016 in Dorchester, the largest and most diverse neighborhood of Boston. Their website says “Our goal is for communities to be able to self-organize SERCs whenever they feel like they need them. We imagine a people-led public infrastructure sweeping the country!” They encourage people to pop up SERC’s in all kinds of venues: “youth programs, art galleries, health centers, colleges, community organizing programs, etc.”

Please share the Guide, tell people about the Salon, and watch this space for more information about the USDAC’s Artistic Response work to come.

Art Became the Oxygen: Free Artistic Response Guide Available Now

What is “Artistic Response?” When USDAC Cultural Agent Dave Loewenstein (of the Lawrence, KS Field Office) visited Joplin, MO in 2011, he was expecting to help community members create a mural about Joplin as part of the Mid-America Arts Alliance Community Mural Project. Joplin was one of half a dozen small towns chosen by competitive application to receive a three-month mural residency. But that May a massive tornado hit, destroying a third of Joplin’s buildings and taking 161 lives. A community arts project turned into an Artistic Response project. You can read all about the Joplin project on pages 23-25 of Art Became The Oxygen: An Artistic Response Guide. Scroll down on the Guide page to enter your email to download the just-published free 74-page Guide.

Artistic Response isn’t just about visual art, nor is it just about storms and other weather emergencies. The phrase describes arts-based work responding to disaster or other community-wide emergency from Katrina to Ferguson, Sandy to Standing Rock. Most of the work featured in the USDAC’s Guide was created in collaboration with community members directly affected by crisis. Most of it pursues one or more of three main objectives: offering comfort, care, or connection in the immediate wake of a crisis; creating powerful images and experiences that amplify and focus protest, penetrating the media and public awareness; and engaging those affected by a crisis in creative practices over time that help them reframe and integrate their experience, building resilience and strengthening social fabric.

Once you download the Guide, be sure to join us at 3 pm PDT/4 pm MDT/5 pm CDT/6 pm EDT on Tuesday, 29 August 2017 for an Artistic Response Citizen Artist Salon featuring Carole Bebelle, Co-founder and Executive Director of Ashé Cultural Arts Center in New Orleans; Mike O’Bryan, Program Manager in Youth Arts Education at the Village of Arts and Humanities in North Central Philadelphia; and Amber Hansen, a visual artist based in South Dakota and Co-Director of Called to Walls. Just enter your email to sign up and you’ll receive a link to take part in this online video conversation.

In Art Became The Oxygen, Gregory King says of his 2014 experience with Dancing for Justice in Philadelphia:

On December 13th, I stood next to a white person dancing next to a black person in protest of the grand jury’s decision not to indict Officer Daniel Pantaleo in the killing of Eric Garner. I saw no discomfort, only dialogue. Dressed in black, red, and white, dancers moved together demanding justice for Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Akai Gurley, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, and so many others.

Carol Bebelle describes the work Ashé Cultural Arts Center in New Orleans did after Hurricane Katrina in 2005:

There are so many things that anchor our existence. To lose them all leaves us on a sea without an anchor. So people were dealing with identity issues. They were dealing with disenfranchisement issues, they were dealing with homesickness. They were dealing with loss in a huge fashion. What we really came to appreciate was the necessity to get some air in the room first before you try and do something else, to get them some oxygen so that they can start breathing. So art became the oxygen.

In St. Louis, De Nichols cautions that:

Artists have to be humble to understand that we can influence things without always having to be in charge or be the “fixers.” Outcomes work out better when we take those ethical steps to listen to community members and have them be a part of the full process.

And Mike O’Bryan speaks of the importance of checking your own reactions in favor of a more generous understanding of what’s going on:

Begin with the end result of someone healing in mind, and using that as an anchor for when things get rough and tough and being able to step back and kind of de-personalize some of the tense moments that people are going through. Hurt people are hurt. It’s hard to remember that sometimes when you are sacrificing and you’re a hurt person who’s trying to facilitate healing as well. So hurt people might do things that hurt. And that’s okay. It took me a long time to learn that.

Theirs and dozens of other voices are heard, with links to a wide variety of artistic response projects and resources. Art Became The Oxygen offers advice on the ethics of artistic response, building effective working relationship, bridging the distance between artists and emergency management agencies—all in the aid of building understanding and engagement in this important (and too often under-valued) work.

After flooding in Queensland, Australia, teens in Ipswich were asked to define resilience. Their responses were projected for the Writing’s Off the Wall project, part of the Creative Recovery Program. Photo © Scotia Monkivitch from Public Art Review.

The Guide was written for a broad audience, including three main categories:

- Artists who wish to use their gifts for healing, whether in the immediate aftermath of a crisis or during the months and years of healing and rebuilding resilience that follow.

- Resource-providers—both public and private grantmakers and individual donors— who care about compassion and community-building.

- Disaster agencies, first responders, and service organizations on call and on duty when an emergency occurs, and those committed to helping over time to heal the damage done.

Please share the link, tell people about the Salon, and watch this space for more information about the USDAC’s Artistic Response work to come.

Citizen Artist Salon: Policy on Belonging

Charlene Martinez: Curating Possibility and Cultural Organizing at Oregon State University

I think I learned this from USDAC: when people are able to speak their voices into a space, whether it be an event or an activity, the sooner people are able to do that the more they then feel invested in the process and in other people. There’s something about that that’s really important and special.

Charlene Martinez

A people-powered department has to engage people where they are and mostly when they are juggling many responsibilities. Working with allies in higher education is a natural: students are learning to navigate and negotiate multiple identities; faculty members are teaching and counseling students many areas touching on culture, whether in arts programs, community development, social work, history, education, or other academic specialties. How—and why—do you make space in a crowded institutional framework for the USDAC?

Chief Policy Wonk Arlene Goldbard spoke with Charlene Martinez, Associate Director of Integrated Learning for Social Change at Oregon State University’s Office of Diversity & Cultural Engagement, and a member of the USDAC’s third cohort of Cultural Agents. At OSU and elsewhere, Charlene has been remarkably successful in integrating elements of the USDAC such as Story Circles, a simple, powerful dialogue method that has been the centerpiece of National Actions such as the People’s State of the Union; and Imaginings, art-infused community dialogues toward a shared and inclusive future vision.

Arlene Goldbard: How did you get involved in the USDAC?

Charlene Martinez: I found information on some listserv about #DareToImagine (a USDAC National Action in October 2015). Around the same time I saw the call for Cultural Agent applications. [NOTE: In 2014-2016, the USDAC selected three cohorts of Cultural Agents to take part in a national learning community and host an Imagining in their communities.] After I became coordinator for the Arts and Social Justice Living Learning Community [an on-campus residential program], I started doing my own research on what was out there in terms of arts and justice work. So the impetus was really that I didn’t know enough. I wanted to be part of a learning community. I wanted to do well by my students. And that’s why I signed up to be a Cultural Agent.

I started reading more on the website. I loved the principles; loved all of the values; loved the ideas and the actions. But at that time I actually didn’t know what I was applying for! I thought it was a governmental agency, even though it says everywhere that it’s a people-powered department.

I think the interview sold me: meeting Yolanda Wisher and Adam Horowitz online and hearing more about what the USDAC was right at the same time I was learning about my own work. There were so many possibilities and so many connections with the work I was trying to do on campus.

Arlene: Say more about that.

Charlene: The biweekly USDAC online learning calls for Cultural Agents were one thing that not only inspired me to do more work in this area, they actually helped retain me here at Corvallis, at Oregon State. I came in seeking a community. I didn’t know how to activate my own skill sets here that I had brought from California. I didn’t know how to relate to my peers here.

The process not only supported my ideas of cultural organizing but helped me relate better to the people here. It gave me greater hope through what I was seeing from Cultural Agents all over the nation. I’ve learned so much from every individual and the way that they showed up, and I am truly grateful for that.

One of the things that I shared with a lot of Cultural Agents was that there wasn’t a competition of ideas. Universities like to do things a very particular way; innovations aren’t always welcome. So being in a community filled with people who are either artists or have an art base, they automatically live and breathe that. To be part of that culture and part of that community felt really rich to me, warm and exciting.

The USDAC helped me realized that maybe the outreach that I was doing was too small. Maybe I needed to try things on with other colleagues that I had never tried it on with before. And then it started to work. I started to see things ignite in different ways.

Arlene: Unlike many Cultural Agents, you didn’t come to it from a primary art practice. The USDAC isn’t just for artists by any means, but I’m interested in how we bridge between artists and others. How was that?

Charlene: It was a little intimidating at first to not have an art discipline I was coming with. But I learned that one of my aspects and strengths was in curating—not curating in a traditional sense, but with ideas or with people. I hadn’t known the terms, I didn’t know the players, but I’ve been doing the work, right? I’ve been facilitating the artists that come in. I’ve been doing the cultural organizing. I just didn’t have the terms for it.

Arlene: That’s something we’ve heard a lot. I keep thinking there might be a key in your experience to this larger question of how we get people interested in culture as a container or a crucible for organizing who just who may not be oriented that way.

OSU Imagining 2016

Charlene: Language and concepts from the USDAC helped me change my framework. Instead of offering a class that was a survey of arts activism it turned into “Where is your agency? What do you care about?” We move through the world in this culture. Not in a politic necessarily, but in a culture, and we all have culture. When I heard the USDAC principles—everyone has a right to culture, everyone has a voice—it’s all the same things I’ve done in my work in higher education, but higher ed wouldn’t approach it that way. It would be all about others coming to learn about this program, not how do I activate everyone to teach where they are and wherever they’ve entered in this conversation—whether that’s around blackness, for example, or food and class.

Arlene: I understand you’ve used Story Circles in many ways on campus since you encountered them in the USDAC.

Charlene: I began using the Story Circles tool with People’s State of the Union 2016. I started with the class I was teaching for that quarter, an arts and social justice class. We tried on the PSOTU as one of the first assignments. I created a flyer and did the groundwork of organizing students to get other people to come to the Story Circle. The focus of that program was around the experiences of being racialized and/or being a first-generation college student.

We only had around ten people come to that. But what was awesome was we trained the facilitators who ended up being the participants of that day and that’s what kick-started a lot of different, interesting Story Circle happenings. Two students who were in that class decided to take the Story Circles platform and create their own projects. One student was an Ethnic Studies major, the other an Art major. They became inspired by the process. So within that ten-week class period they then brought together their own communities, the Chicanx/Latinx, and Hmong students, and found they had so much more in common than they thought. They told stories of immigration and assimilation. It became this snowball thing: wow, this model really works, and it’s kind of like inter-group dialogue, but it doesn’t need to be as prolonged or sustained. Story Circles have consistently helped us slow down; helped us build with each other; helped us see the commonalities and really listen for the places that we’re very different.

I’ve taken Story Circles now on the road to many different places. One of them was Promise, an Oregon State internship program, a pipeline program for historically underrepresented students to learn about civic professionalism through summer internships. The president of the university usually comes in and does a talk to the students, then there’s a short Q&A period and it’s over. Many of the students are juniors and seniors. They’ve been around at OSU for a while. They wanted something different. So we changed the format to a Story Circle session. President Ed Ray, along with a visiting guest from the Federal University of Abeokuta, Nigeria, Fehintola Nike Onifade, rotated through two cycles of different circles of students telling their stories about inclusion and exclusion at OSU. That broke down a lot of the power dynamic and barriers.

OSU Imagining 2016

Arlene: What advice would you have for other people who are working in higher ed?

Charlene: Story Circles can be one of the keys to the door but people still have to walk through. What do we create together based on that? First year students of the arts justice community here along with the cultural center leaders planned a series of open mics after the Story Circles. They were really engaged in getting the right people there and figuring out what messages to communicate. They ended up doing some great poetry. One open mic was right before election; one was right after. Both had completely different energies because one was in the Women’s Center and one was in the Asian and Pacific Islander Cultural Center. A lot of the artwork came from the Story Circles we did in class. It was so powerful for the students to be able to express themselves during this really intense period. They’re also in a place of identity exploration—gender identity, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, all of those things—and not feeling like this country can really hold them. And here they are carving out a space to say no, we’re going to build this container for myself and other people who feel this way. Since then, student leaders I work with have presented about Story Circles at a students of color conference. It’s gaining traction.

It’s important to dig deeper into figuring out how we can be organizers, not just producers of student leadership or programs. The language I would like to share with others is that these moments can be critical sites for intervention to shift culture. And to not be afraid of the pushback that you will receive, because you will receive it.

Imaginings have been like that for us too. For the MLK, Jr. holiday in January, the campus celebration week ended with an Imagining. It was also Inauguration Day. That was so powerful: this group of people—I don’t know if they were inspired by the Imagining I did as a Cultural Agent or not, but these things are iterative. Once we get the flavor and people get inspired by it, then they just take it on and do what they need to do for their own communities or for their own programs. It was institutional, the Office of Institutional Diversity helped put the MLK week events on with a committee, ending on inauguration day with an Imagining. That is so powerful for me.

Arlene: And for us. Many thanks for all you do!

Citizen Artist Salon: #RevolutionOfValues

2017 People’s State of the Union: “Stories Need to Be Told”

by Arlene Goldbard, Chief Policy Wonk

“Torhala, a senior at Roosevelt High School who is Muslim, spoke about a time during the presidential campaign when she and her mother were driving in the metro. A car pulled up and its passengers yelled ‘Make America Great Again,’ she said, and then told them to ‘go back to where we came from.’”

“’I was fearful that people would spit on me again, that people would laugh at me when I speak English, and that people would tell me to leave again on a boat,’ Nguyen said. ‘But deep in my heart I know that we are a great country and we are inclusive.’”

Rizan Torhala and Vinh Nguyen, quoted in the Des Moines Register

For this year’s People’s State of the Union (PSOTU), most Story Circles took place between 27 January and 5 February. There were hundreds of events around the nation, from a few friends sharing stories across a kitchen table to dozens gathered in a public setting, perhaps meeting for the first time. In this third iteration of the USDAC’s annual civic ritual, tellers were invited to share first-person stories in response to three main prompts:

- Share a story about something you have experienced that gave you insight into the state of our union.

- Share a story about a time you felt a sense of belonging—or the opposite—to this nation.

- Share a story about a time you broke through a barrier to connect with someone different from yourself or with whom you disagreed.

Anyone who wished was invited to upload a story to the PSOTU 2017 Story Portal. Check it out: you will find hundreds of stories from people of many ages, races, locations, genders and orientations throughout the U.S.

In Des Moines, Iowa, the event happened on February 20th. USDAC Cultural Agent writer, and musician Emmett Phillips and allies gathered folks in a club space called Noce, offered for community use on a Monday, its dark night. Organizing started when Emmett met with Carmen Lampe Zeitler, the long-serving former director of Children and Family Urban Movement (CFUM), where he works with youth as Program Coordinator.

Carmen’s “love and passion for community building and youth empowerment and giving a space for voices to be heard is very evident,” Emmett told me, “so I’ve always had a lot of respect for her. She called me to meet one morning around election season, sensing all the things happening around that time and wanting to do something about it, but not knowing what. She reached out to Don Martinez, the executive director of an organization called Al Exito which works with Hispanic high school youth. And they also reached out to Larry Christianson who is retired and was more than willing to help us plan things out. This is around the time the USDAC was planning PSOTU. By the next meeting we decided that we wanted to do a Story Circle. After everyone knew exactly what it was, they jumped right onboard with it.”

Photo: Kelly McGowan/The Register

The Des Moines Story Circles began with Emmett emceeing, young people performing poems, and a handful of individual stories presented onstage before sharing began at small tables all around the room. I asked Emmett why they chose to start out this way. “One, to break the ice for everyone, since it’s kind of a new experience just sharing stories. And two, to make sure that the groups that really needed to be included in the conversation got their perspective out first and foremost. We thought it would empower everyone else to be open with what they’ve been through.”

And the poetry? “I work with an organization called Run DSM that has a program called Movement 515 about the urban arts: poetry, graffiti, hip-hop, photography. I’ve done a hip-hop camp and currently do poetry workshops in the middle school with them. They have a lot of young people that are brought up and empowered and trained and rehearsed with poetry. They understand the power in it, and always do a great job. So I reached out to a couple of their poets to come and bless us. We had three different poetic performances, one for the opening and two to close the show.”

I asked Emmett about success factors. “We had great support from the venue. They were courteous. They were there to help us set things up. So the environment definitely played its part. A lot of the people were there off of respect of the people that invited them. It really helps to have like a team where people would follow them wherever they go because they know it’s going to be something good. Starting with poetry was good: a poem from a young high schooler that was very awake and very appropriate, that hit people in their feelings, the emotional investment that says why we’re even here. And the stories had people in tears. A note we took on ways to make the event better is to have more Kleenex handy.”

This year as in previous years, we’ve heard from many participants that Story Circles offer a powerful and simple way to connect people, even those who seem to have little in common. In a Story Circle everyone gets equal uninterrupted time to share a first-person story, usually two or three minutes apiece. Listeners give each teller undivided attention, allowing a breath after each story for it to settle. Those factors often have a large impact in equalizing participation; contrast this to a free-for-all where the loudest or most powerful person hogs the space. After everyone has shared a story, the members of each Circle reflect on what has been revealed by the body of stories.

In Des Moines, once folks in Story Circles started reflecting, it was hard to stop. “Our intention was to have people break into their groups for a little while, then hear from everyone and then do closing poetry. But people were having too much good topical conversation. I just couldn’t stop that. So we let them continue pretty much until we had to leave. People felt really, really open and connected. The event was two hours—it’s crazy that that wasn’t long enough, you know?”

Emmett and his collaborators sent a follow-up question to everyone who took part. A large portion of the participants responded. Forty-two indicated that they’d like to participate in future Story Circles. No one replied to that question with a “no.” The typical response was what we’ve come to expect from PSOTU participants: “Great start. Loved the conversations. Stories need to be told.”

Why is the simple invitation to sit in circles, share stories, and listen fully so powerful? Based on the hundreds of Story Circles I’ve observed and facilitated, two main answers come to mind. First, it can be a sadly rare and remarkably delicious experience to receive full attention, to inhabit the space to tell a story without fearing interruption or contradiction. Too often, people are texting while you talk, or waiting for your mouth to stop moving so their turn can start, or looking over your shoulder for someone they’d rather engage. But the attention and permission of a Story Circle are an antidote to that.

Second, as we say when each PSOTU launches, “Democracy is a conversation, not a monologue.” Too much ordinary public discourse is left to those deemed experts. Too much is conducted in a way that privileges certain types of knowledge—official findings, numbers, the jargon of a particular sphere. What tends to emerge is opinion, and opinion can always be contested. In a polarized moment, many people are made anxious or fatigued by the prospect of a shouting-match fueled by conflicting opinions that fail to persuade. But stories are different. When someone’s first words are, “I want to tell you a story about something that happened to me,” when the sentences that follow tell an actual story, with a beginning, middle, and end, surprisingly few even try to contradict another’s actual experience. Each storyteller’s truth emerges to stand alongside the rest, and when the group reflects on what has been learned, the richness is often unexpectedly powerful.

You don’t have to wait till PSOTU 2018 to try it out. The USDAC’s next National Action, #RevolutionOfValues, is a day of creative action taking place on April, the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s groundbreaking Riverside speech. There are many ways for individuals and groups to take part. Download the free Toolkit and you’ll have access to all kinds of resource, including detailed Story Circle instructions.

#FollowTheMoney #SaveTheNEA

by Arlene Goldbard, Chief Policy Wonk

"A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Learn more at #RevolutionOfValues)

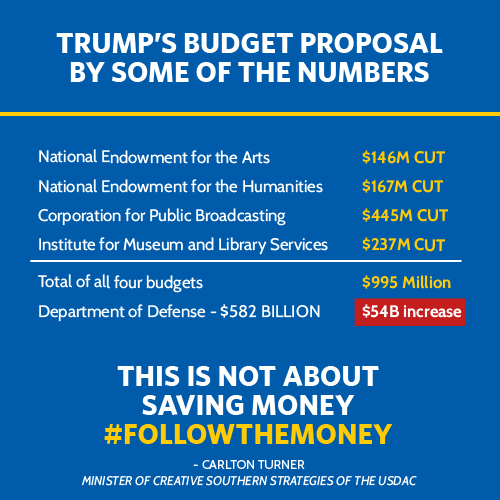

This morning the White House released its proposed budget for FY 2018. The $1.1 billion proposal for federal discretionary spending (which amounts to about a third of all federal spending) calls for deep cuts to many agencies that protect the commonwealth. For example, it chops nearly a third of the Environmental Protection Agency’s budget, and more than one-fifth of State Department programs supporting exchange and development.

But federal cultural agencies—the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services—are singled out for extinction along with other independent agencies that promote international cooperation and address issues such as homelessness, community development, and public safety.[1]

The proposed budget has to go through the Office of Management and Budget and Congress before it can be enacted. You, the taxpayer, can influence whether it breezes through or is blocked by public outrage.

Want to be heard? Write to your elected representatives as part of the Arts Action Fund’s #SaveTheNEA campaign or use the Performing Arts Alliance’s response form. This tool will help you find contact information and background about elected officials: use it to make your own calls or write your own letter.

The President’s budget is at once shocking and unsurprising. He’s making a frightening statement about American values, adding nearly $60 billion to our investment in war—which already amounted to three annual NEA budgets a day, seven days a week. For reasons far more symbolic than cost-cutting, he wants to eliminate the small programs that help us know and understand each other, those that make the constitutional commitment to freedom of expression real, for what does it mean to declare a right without the means to exercise it?

Here are some of the facts Carlton Turner, Minister of Creative Southern Strategies on the USDAC National Cabinet, posted to Facebook this morning with the hashtag #followthemoney:

I wish mainstream arts advocates talked less about economic impact and much more about who we are as a people, what we stand for, how we want to be remembered, because that’s what is endangered here: the value of beauty and meaning to the body politic. We urge everyone to stand for cultural rights and cultural freedom—for the public interest in art—against a White House that considers them dispensable.

The quotation at the head of this blog is from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Riverside speech, “Beyond Vietnam: Time to Break Silence,” delivered fifty years ago on April 4, 1967. In the speech, Dr. King calls for a “a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society.” Presented with this thing-oriented budget proposal—far more oriented to such things as guns and bombs than to the well-being of communities and families—, it is our obligation to stand for love and justice, walk in Dr. King’s footsteps, giving voice once again to his powerful words, and reminding people of his real message and unfinished work. Join us:

- Enlist as a Citizen Artist to join the people-powered USDAC in year-round learning and action to make cultural democracy real. You’ll be the first to know about actions, events, and resources you can use.

- Download the free #RevolutionOfValues Toolkit to join people across the nation in drawing inspiration from and breathing new life into the prophetic words Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., shared one year to the day before he was assassinated. The Toolkit will give you everything you need to take part in #RevolutionOfValues, a national Day of Creative Action on April 4th.

- Join our free, online video Citizen Artists Salon on Wednesday, 22 March, at 3 PDT/4 MDT/5 CDT/6 EDT when fiercely creative activists from three generations share their wisdom and inspiration in preparation for April 4th.

The release of this budget proposal is the just first shot in a battle over investment in cultural rights, human rights, equity, and social and environmental justice. Public response can turn the tide, not only from ordinary citizens who cherish cultural rights, but from all those big Republican donors who support arts organizations. If the White House won’t listen to parents whose kids benefit from arts in education or neighbors who love their local arts center, perhaps they’ll listen to the people the rest of their policies seek to profit. Let them hear your voice:

Write to your elected representatives as part of the Arts Action Fund’s #SaveTheNEA campaign or use the Performing Arts Alliance’s response form. This tool will help you find contact information and more about elected officials if you want to write your own letter.

[1] Including the African Development Foundation; the Appalachian Regional Commission; the Chemical Safety Board; the Corporation for National and Community Service; the Corporation for Public Broadcasting; the Delta Regional Authority; the Denali Commission; the Inter- American Foundation; the U.S. Trade and Development Agency; the Legal Services Corporation; the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation; the Northern Border Regional Commission; the Overseas Private Investment Corporation; the United States Institute of Peace; the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Building Democracy in "Trump Country"

NOTE: Ben Fink, who authored this essay, is creative placemaking project manager at the Appalshop; he grew up in Connecticut and now lives on Little Cowan in Letcher County. He holds a Ph.D. in cultural studies from the University of Minnesota. He’s taught school in Minneapolis and Berlin, directed youth arts programs in New Jersey, and consulted with homeless service nonprofits in Connecticut. You can find him at the nearest shape note singing, or follow him on Twitter at @benjaminhfink. This piece, which was first published on BillMoyers.com, originated in his presentation at CULTURE/SHIFT 2016, the USDAC's national convening held in St. Louis in November, 2016.

Appalshop program participants filming. (Photo by Shawn Poynter Photography)

A lot of people don’t believe me when I tell them Letcher County, Kentucky, is one of the most open-minded places I’ve ever lived.

I moved here a year ago. I’ve spent most of my life in cities and suburbs, and I arrived with all the assumptions you can imagine about Central Appalachia and the people who live here.

I might not have believed it either, before I moved here a year ago. I’ve spent most of my life in cities and suburbs, and I arrived with all the assumptions you can imagine about Central Appalachia and the people who live here.

But if you’ve been here, or to similar places, you know how wrong those assumptions can be. Yes, some people fly Confederate flags. One of them, down the road, used to share a front lawn with an anarchist environmentalist, and they got along fine. Yes, my northeastern accent sticks out. And as long as I’m open about who I am and interested in who they are, I’ve found almost everyone here is ready to open up, take me in and work together.

Letcher County went 79.8 percent for Donald Trump. He won every county in Kentucky, except the two that include Lexington and Louisville. Around 3 a.m. on election night, I woke up in a panic as three celebratory gunshots from next door shook my house.

The next morning it was hard to get out of bed. Was this still the same loving, open-minded place where I went to sleep last night? Did I belong here anymore?

Bill, Letcher County Volunteer Fire Chief (Photo courtesy of Lafayette College/Clay Wegrzynowicz ’18)

My phone rang; it was Bill. Bill is fire chief in one of the remotest, poorest parts of the county. He and I had worked together a lot over the past year, most recently on a project to get energy costs down at the county’s cash-strapped volunteer fire departments. Bill and his crew do a lot more than fight fires; they look after sick neighbors, get food to hungry families and otherwise work day and night to take care of their community, for no pay.

Still, Bill isn’t your average partner for a social justice-oriented nonprofit. He’s a former logger and mine owner. He’s campaigned for some of the most right-wing candidates in the area. And his interactions with public officials have been, well, colorful.

I let the phone ring. I didn’t think I could talk to Bill that morning. He was going to be happy and peppy — he’d just won, after all — and he’d ask me how I was. What could I say? I’m doing bad, Bill. Four-fifths of this county just elected someone really scary.

Letcher County went 79.8 percent for Donald Trump. He won every county in Kentucky, except the two that include Lexington and Louisville.

Finally, I called him back. He greeted me as always: “Why hello there, young feller! How’re you this morning!” I hesitated: “Honestly, I’m not doing great.”

Turns out he wasn’t either. His close friend and longtime secretary was dying of cancer — and without her help, he’d need a few more days to find the power bills I’d asked him for. I told him of course, take the time you need, and that I was very sorry to hear the news. She would die a few days later.

The Appalshop, in Letcher County, Kentucky. (Photo courtesy of Appalshop)

I work at the Appalshop — originally short for “Appalachian Film Workshop.” We were founded in 1969, with funding from the federal War on Poverty and the American Film Institute, as a program to teach young people in the mountains to make films. A few years later, when the government money stopped, some of those young people took it over and re-founded it for themselves.

Ever since, it’s been a grass-roots multimedia arts center: a film producer, theater company, radio station, record label, news outlet, youth media training program, deep regional archive and sometimes book and magazine publisher. It’s put the means of cultural production in the hands of local people.

At the Appalshop, we work with stories. Stories are how we learn, how we make meaning out of our lives, how we understand who we are and what we can do, individually and together. The story of Appalachia, as told in so many reports from “Trump country,” tends to be pretty depressing: broken people, victims of poverty and unemployment and addiction, clinging desperately to a divisive and hateful politics as their last hope.

My phone call with Bill, like so many other moments I could describe, hints at a different kind of story. A story suggesting that even after Election Day, we might not be as divided as we think. That even those who feel like we “lost” the election could ultimately win, together. And that if what we’re doing works here — listening to each other, caring for each other, working with each other on common ground toward common goals — it might work in other places, too.

If what we’re doing works here — listening to each other, caring for each other, working with each other on common ground toward common goals — it might work in other places, too.

One thing that’s different about Appalshop, compared with a lot of nonprofits, is we don’t do “community engagement” or “community outreach.” We aren’t looking to “help” or “save” the community. We are part of the community, no less and no more. One day, several months into my job, my boss pulled me aside and told me to stop starting sentences with “I’m not from here, but….” “You are from here now,” he said.

Of course, not everyone else from here loves what we do. I hear the term “Appalhead” now and again; I’m told it was real big five years ago, at the height of the so-called “Obama War on Coal.” It’s easy to call out the misinformation behind the label. No, we’re not all from New York and San Francisco; more than half of us grew up here. No, we’re not marching in liberal lockstep; our staff meetings can involve heated political debate. And no, we don’t hate coal miners; but industry executives and their political allies would like folks to think we do.

Still, if I lost a well-paying job when a mine shut down, and I saw people who claimed to be from my community raising money to make a film about how awful strip mining was instead of doing something to try to help my family, I’d probably be resentful, too. That resentment, I think, is a lot of what this election was about. County by county, the electoral map of the whole country looked a lot like Kentucky. Urban went Clinton. Rural went Trump. Rural won.

For those of us who don’t like how the election turned out, we’re left with two choices. We can keep ignoring or ridiculing the resentment my neighbors feel, and calling them ignorant and otherwise illegitimate for the ways they think, talk and act. And we’ll keep getting the same results. Or we can listen and try to understand where they’re coming from, even when we don’t like it, and see what we can build together.

Because either way, in this election we learned that rural people have power. Whether we like it or not.

In this election we learned that rural people have power. Whether we like it or not.

The work I do is rooted in the Popular Front of the 1930s, when people came together across all kinds of differences to build power and fight against fascism. They understood power very simply, as organized people plus organized money. Since then, some organizers in this tradition have added a third term: organized ideas.

That’s the formula I use every day: Power = Organized People + Organized Money + Organized Ideas.

If we want to understand the power in rural America and how it can be organized differently, first we need to know — who’s got it? Who, exactly, has been doing the organizing?

The answer is, as usual: not us. The bigotry and violence of the Trump campaign wasn’t the product of our people, money or ideas. My neighbors may not be up on the latest social justice lingo, but they are not hateful.

No, the organizing took place far away. What we get, on both sides, are the bumper stickers, the prefab identities sold by the people with power to make us feel powerful — even as they use our power for their own benefit.

(Photo by Mimi Pickering)

During the election our county was full of “Trump Digs Coal” signs, but the week afterward the top headline in our newspaper The Mountain Eagle was: “Don’t expect jobs mining coal soon, McConnell warns.” Again, though, if you’re a coal miner who lost your job and you’re convinced Obama is to blame, it makes sense that a sticker on your car could make you feel better. Like you’re fighting back.

So we’re left with the all-too-familiar story of “us” versus “them.” “Our” “good” bumper stickers — and energy-efficient foreign cars — versus “their” “bad” ones — on a clunker to boot.

The bumper that gives me hope, though, is the one parked in front of our building the day after the election. It had a “Make America Great Again” sticker and a sticker for WMMT-FM 88.7, the community radio station run by Appalshop, which broadcasts news and music across central Appalachia and streams worldwide. WMMT has 50 local volunteer DJs, from all political positions.

Old Red on the mic at WMMT-FM 88.7, the community radio station run by Appalshop. (Facebook photo)

Including this guy. Old Red hosts the First Generation Bluegrass show on Thursday mornings. He plays great music, has a terrific radio personality and likes to make fun of Al Gore on the air. When I hosted a show last summer, I went on right before him.

One morning I played “Pride,” a haunting song by Ricky Ian Gordon about a gay man discovering he has AIDS and finding home in the uprisings of the mid-1980s. Near the end of my show Red came into the studio, as usual, and put down his pink bag. “I heard that song you played while I was driving in.” I took a breath. He continued: “I don’t know a lot about this stuff. I think I know what ‘L, G, B, T’ means, but I’m not sure about ‘Q, I….’ Can you help me?”

When Red steps into that studio, he feels safe enough to admit he doesn’t know something, and learn. Even from someone like me. Because that studio is a place Red knows he belongs. He gets to broadcast his music, his voice and his ideas, whatever I or anyone else might think of them, to five states every week. Just like scores of other people — including relatives of folks locked up in nearby prisons, who call in to our weekly hip hop show “Hot 88.7 — Hip Hop from the Hilltop and Calls From Home.” We can’t always see them, but they are part of our community, too.

Economist Fluney Hutchinson (Photo courtesy of Lafayette College/Clay Wegrzynowicz ’18)

A few years ago, with the coal economy on its last legs, a new generation of Appalshop leaders started working with a Jamaican economist named Fluney Hutchinson. Fluney has done development in poor areas across the world, sometimes with the International Monetary Fund.

But he doesn’t work through loans, austerity and government takeovers. He works, basically, through organizing. Or as he puts it: “Strengthening the capacity of residents to exercise voice, agency and ownership over their community affairs is essential to their ability to create communities that they value.”

He recognized Appalshop was already doing this, through radio and theater and other media. But he asked, how could we do more? How could we help build an economy where everyone had voice, agency and ownership? Where we can work and act and vote out of hope for a future we’re working to make, instead of out of fear of a future we feel powerless to stop?

This is what we came up with:

(Image courtesy of Appalshop)

Basically, Appalshop would use its resources and relationships to do broad-based organizing. We would build a wide network of grass-roots organizations working to strengthen people’s voice, agency and ownership, starting in Letcher County. Each organization in our network would support everyone else’s work, connect each other with resources, plan projects to bring value and wealth into our communities, and bring together organized people, money and ideas.

What does this look like? It looks like a remote community center getting the support to reopen the longest-running square dance in the state of Kentucky, with guests from around the state and around the country.

It looks like the county volunteer fire departments, led by my buddy Bill, working together to start an annual bluegrass festival that made $10,000 in its first year.

It looks like starting Mountain Tech Media, a new cooperative for-profit corporation, under Appalshop’s roof. And at the same time, working with our regional community and technical college to start a certificate program in tech and media skills — to create a complete community-based pipeline to employment for young people in the area.

It looks like people and groups of all kinds coming together and recognizing that we have power, and together we can build more. That we don’t have to wait to be saved. That we can create markets on a scale to attract the attention of investors — and keep the value of those investments in our community.

It looks like a certain drink at the new Kentucky Mist Moonshine, Letcher County’s first legal still, run by a Republican businessman who’s now a close partner in the Downtown Retail Association we helped found. It involves apple pie moonshine, cider, a little sour mix, cinnamon, sugar and apples. They call it the “Appal Head.” (They made me a free one recently; it was delicious.)

And it looks like the young girl who recently came to a painting party hosted by our youth media institute. She said she’d wanted to come for a while, but she was nervous because she didn’t know anyone. Before she left, she left a note with the Institute’s director:

(Photo courtesy of Appalshop)

At the start of 2017, Appalshop is 48 years in (and still learning, of course). But I think we’re onto something. When we work together to make places where we all feel like we belong, we can feel safe enough to open ourselves to people and ideas we might otherwise fear. When we build a culture and economy based on shared agency, voice and ownership, we can live with dignity and own the value we create. That’s what we’re imagining here in Letcher County, Kentucky.

Can a project started in Letcher County go nationwide? We’re ready. Want to work with us? Let’s talk. We like visitors. Above the doors of our local library, in the words of Letcher County author Harry M. Caudill, is our standing invitation to all:

(Photo courtesy of Lafayette College/Clay Wegrzynowicz ’18)

The Space Between Imagining and Making Real Is Very Small

NOTE: On Saturday, 21 January 2017, Judy Baca, Minister of Sites of Public Memory on the USDAC National Cabinet, delivered these inspiring remarks to 750,000 marchers at Los Angeles' Women's March.

Hello marchers! Hello Angelitos! Welcome to the official inauguration of President Trump!

My name is Judy Baca and I am cofounder of a woman-founded arts and social justice organization—SPARC—that has been fighting for human rights for 40 years.

For me today all of you are the best news I have heard since November. I look out and see every generation that has historically stood for justice on every front, united today. And perhaps that is what we must be grateful for at this heart-clenching moment.

We outnumber by millions those who would make America whites-only again. Remember that we once stopped a war. We changed profoundly women’s roles in society. We fought for acknowledgement and fair treatment of immigrant laborers in our nation of immigrants. We pressed for the rights of the LGBTQ community.

What is important at this moment is to not underestimate the powerful role of artists. Witness all of our pussy hats, handmade, behind them are hours of people making them. It is our job as artists to:

- visualize in the broad strokes of a brush,

- to articulate in the spoken word or the stories we tell,

- to lift hearts with song; and

- to create a vision of a humane and just world.

In my 40 years as an activist artist at SPARC I have come to understand that the space between imagining and making real is very small. Together, we can imagine and make real the vision of a country that is respectful of all its people, particularly women and of Mother Earth that gives us our very life. To quote our former President, “In our increasingly interconnected world, the arts play an important role in both shaping the character that defines us and reminds us of our shared humanity.”

Each day that passes, with each egregious action of the Trump administration that would dismantle all of our hard-won progress, it is important to know that we need to resist each attack one by one and stop every action, every move toward fascism. And we must do it sustainably, with joy and certainty that we can and will win.

We are already seeing the beginnings of official actions by the current administration to undermine all that we have worked for. We cannot allow these backward hateful, misogynist, racist, ideas to become the new normal. This is not normal. The building of walls, actual or metaphoric, forecasts a future of division between peoples.

I remind us that the only wall that should be built is the one we build with our bodies and our resistance against the destruction of our dignity and our democracy.

Jae C. Hong/Associated Press

Symbolic Gesture Comes Out of Retirement

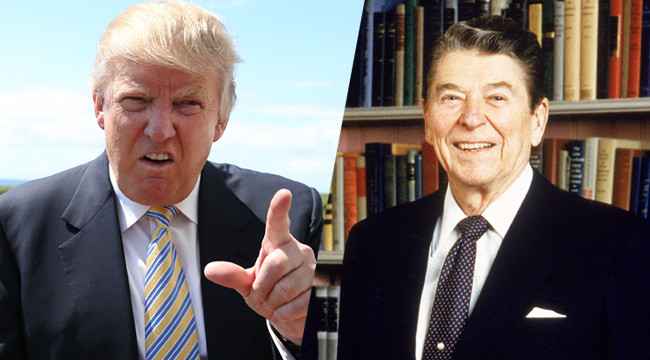

Washington, DC, January 20, 2017. Advisors to the incoming presidential administration have pulled a bald and creaking Symbolic Gesture from a storehouse of anti-art props left over from the Reagan years, it was announced yesterday. Citing the need to reduce spending, Trump spokespeople from the ultra-right Heritage Foundation started a rumor that “The Corporation for Public Broadcasting would be privatized, while the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities would be eliminated entirely.”

As The Washington Post explains:

The NEA’s current budget is $146 million, which, according to the agency, represents “just 0.012% … of federal discretionary spending.” The NEH also has a budget of $146 million. The CPB receives $445.5 million. By comparison, the budget for the Department of Defense is $607 billion.

And that Defense budget includes military music groups, allocated more funding than the NEA.

The last time such purely symbolic cuts were threatened was when Ronald Reagan took office in 1980, armed with a Heritage Foundation policy directive also entitled Mandate for Leadership, as is the current three-part Heritage manual for the new administration.

In an exclusive conversation with Norman Beckett, the Deputy Secretary of the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture, Mr. Symbolic Gesture (or SG, as he likes to be called) explained the Heritage-Trump maneuver. We caught up with him in a suite at the Ritz-Carlton, soaking in a hot tub to get out the kinks.

SG: Wow, you’d think they’d be more original [bone-rattling sigh]. I can barely get around after 37 years in storage. But at least everyone knows the drill: threaten to cut something beloved that’s the size of a gnat, inflate your accomplishment in the media, lotsa bang for almost no bucks—and you know, I’m a master of misdirection. While everyone is busy with this, no one will notice the tax cuts and special deals for the one percent.

Beckett: But isn’t there some legitimate concern that you might not just be Symbolic this time around?

SG: Listen, I don’t know if they’ll ever turn me into a Real Gesture, but I do know what they want—and that is to scare you shitless and make you feel like there’s nothing to be done. Is it working?

Beckett: Not really. We’re organizing!

SG: Oh yeah? But aren’t you just a Symbolic Gesture yourself?

Beckett: Well, the USDAC has no federal line-item, if that’s what you mean. But the best thing about having no official U.S. Department of Arts and Culture as part of the federal government is that there is no incoming billionaire to dismantle it! As a people-powered department, it’s the time, energy, and passion of artists and creative organizers nationwide that drive our mission of inciting social imagination to shape a culture of empathy, equity, and belonging.

SG: Clever, but how do you renew that resource when everything is looking old and orange? Hey...this new guy isn’t Reagan reanimated, is he?

Beckett: We just get more creative. To quote Maya Angelou, “You can’t use up creativity; the more you use, the more you have.” Look, we don’t know what lies ahead for the NEA, NEH, and CPB, but the USDAC will do all it can to stand to protect, expand, and improve our national investment in creativity and communication. We are staying right here to build people-power and remind Citizen Artists across the country that we possess powerful weapons of mass creation.

SG: Weapons of mass creation? Sounds symbolic!

Beckett: Nope, real. To get started, enlist as Citizen Artist—you don’t have to be a U.S. Citizen or an artist. Download Standing for Cultural Democracy to get ideas for policy and action initiatives you can push at the local level. Join us for the People’s State of the Union, kicking off in just one week. And stay tuned for powerful new modes of organizing in the coming months.

We may not have a Secretary of Arts and Culture, but we have each other. As writer Ursula LeGuin reminds us: “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable—but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art.”

SG: Wow. I’m kind of glad they woke me up. Maybe this maneuver won’t succeed any better than the last time those bores at Heritage dragged me out. And then I’ll enlist in the USDAC!

Graphic by Janina A. Larenas. January, 2017.

CULTURE/SHIFT 2016: Recap

Many months ago, when we joined with the St. Louis Regional Arts Commission to plan the USDAC’s first national convening, CULTURE/SHIFT 2016, we chose dates closely following on the November 2016 U.S. presidential election. No one had a clue what the outcome might be (or even who would be the candidates), but we knew that whatever came, it would be a good time to be together.

That turned out to be a huge understatement. As USDAC Chief Instigator Adam Horowitz said in his opening night talk:

Now is a time to be together and however you are arriving in this moment, you are welcome. We welcome those who are grieving, those who are hurting, those who are fired up, those who are searching for that fire. We welcome your uncertainty, we welcome your rage, your courage, and your hope. We welcome your anger and we welcome your love. We welcome your big hearts, and your audacious imagination. We welcome your ancestors, we welcome your laughter, your tears, your dreams. We welcome your paradoxes, your vulnerability, your care, and your questions. We welcome all of you, and all of you. Because we need all of us more than ever.