by Arlene Goldbard, Chief Policy Wonk

#DareToDream takes off on 27 October—designated #DareToDream Day—when “every creative citizen in Scotland is invited to share a dream for the future on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram using the campaign hashtag.” To get an idea of the scope of this national action, check the Facebook event page or the map for local events happening between now and the end of November, engaging an impressive list of partners. Check the resources page for a range of great tools. “There are lots of different ways you can join in with the #DareToDream campaign. Dreams can be wee or huge, and absolutely everyone can take part, in any language!”

#DareToDream is part of the annual Scottish Storytelling Festival, sponsored by TRACS (Traditional Arts and Culture Scotland), and directed by Mairi McFadyen, National Storytelling Co-ordinator of the Scottish Storytelling Forum, “a diverse network of storytellers, organisations and individuals supporting Scotland’s vibrant storytelling community.”

Even though #DareToDream will happen halfway around the world, there’s a USDAC connection. As the website says, “Our #DareToDream campaign is inspired by the #DareToImagine campaign in the US, sponsored by the people-powered U.S. Department of Arts and Culture.

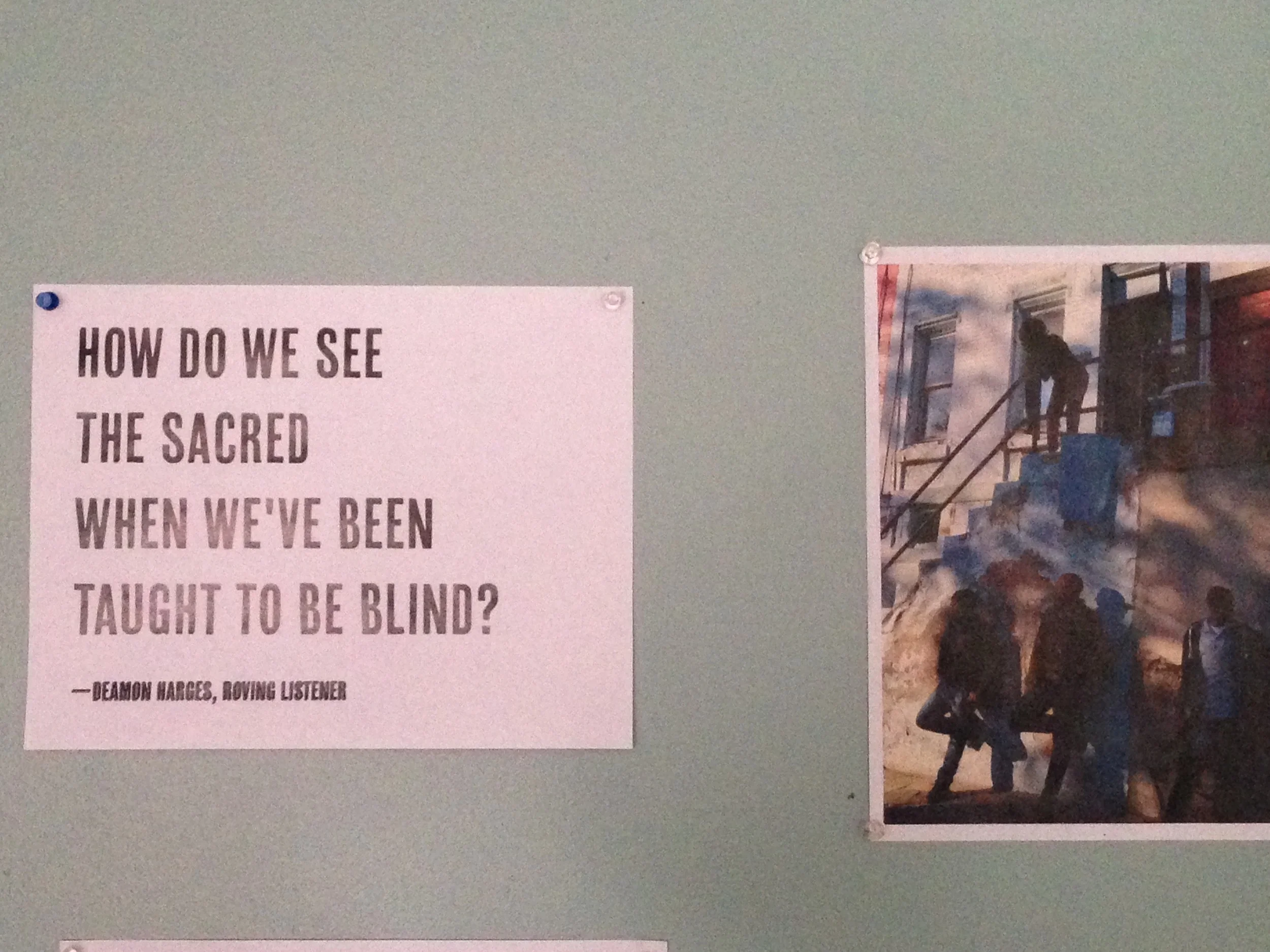

One of the ways #DareToDream expands on storytelling is to invite stories in the form of images and songs as well as narratives, reflected in the accounts populating the #DareToDream blog. Storyteller Beth Cross starts her contribution to the blog with a beautiful quote from Brenda Ueland of Hands on Scotland: “Why should we all use our creative power? Because there is nothing that makes people so generous, joyful, lively, bold and compassionate.” (I was honored to be asked to contribute an essay to the blog as well.)

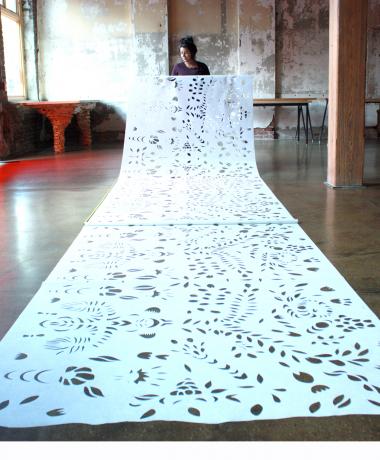

Storyteller Lizzie McDougall and community members working on the Gold and Silver Darlings Story Quilt, a visual celebration of over 30 traditional stories from the North and Inner Moray Firth in the Scottish Highlands.

On a more personal note, I know it’s a big generalization, but: Scotland is cool. And that makes me very curious to see the stories #DareToDream inspires. With a population of just over five million (New York City alone comprises 8.5 million) and an incredibly rich cultural life, things happen on a remarkably accessible and participatory scale. For instance, the September 2014 referendum on independence for Scotland lost 55-45 percent, with a phenomenal 85 percent of eligible voters (which for the first time included those 16 and older) taking part, as compared to the less than 29 percent of U.S. voters who cast ballots in our recent Presidential primary, the most hotly contested race in living memory.

When I visited Scotland well over a year before the independence referendum, everyone I met was already debating the pros and cons of independence from Britain—and telling stories to back up their opinions. (If you want to wonk out a bit, check out my blog on Scottish Culture Secretary Fiona Hyslop from June 2013.) And when the rest of the U.K. voted by a narrow margin for Brexit in June, withdrawing from the European Union, 62% of voters in Scotland opposed withdrawal. Hyslop, whose full title is Cabinet Secretary for Culture, Tourism and External Affairs, has been working hard to keep Scotland in the EU.

What stories of Scotland’s future will be shared in #DareToDream? The USDAC salutes our friends in Scotland for an incredible national action! We’ll be following closely through the end of November.